By Warwick McFadyen

The minister was reflecting on . . .

I must say we are very lucky in this lucky country to have ministers who can pause, and reflect upon, upon matters. That they are able to do so while they are at work – that is, in the cauldron of federal parliament - is even more commendable.

The speaker who observed that the minister was reflecting was none other than the Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull. He was defending his Immigration Minister Peter Dutton.

Mr Dutton had merely made the point that a previous government, one led by a giant of conservative politics Malcolm Fraser, had made a mistake by letting people into the country who were Lebanese Muslims, and that now, a couple of generations, later some of their offspring – grandchildren and children – were reprobates. Of 33 people charged with terrorist offences, 22 were the rotten fruit from this 1970s mistake. These people were besmirching the good name of the Lebanese-Muslim community.

Mr Turnbull’s full quote, in response to a question as to whether he supported the point was this: “There is no question that there are lessons to be learned from previous immigration policies and the minister was reflecting on … policies many years ago. He’s entitled to do that.”

And just to elevate the allegiance to thralldom, he offered the observation: “Peter Dutton is doing an outstanding job as Immigration Minister.”

Well, he would say that, wouldn’t he?

Even allowing for that naked statistic, it is really of no more use than oiling the machinery on which far too many political and social groups try to drive their agendas. The merging of migration policy and malfeasance is contemptuous, but it is part of a broader picture of Australia that is not pretty. Indeed, it’s ugly, painted with strokes of spite, political opportunism, hypocrisy, a lack of decency and fair-mindedness. And above all, racism and xenophobia. Splash a bit of redneck patriotism onto the canvas, and there you have it. Welcome Down Under.

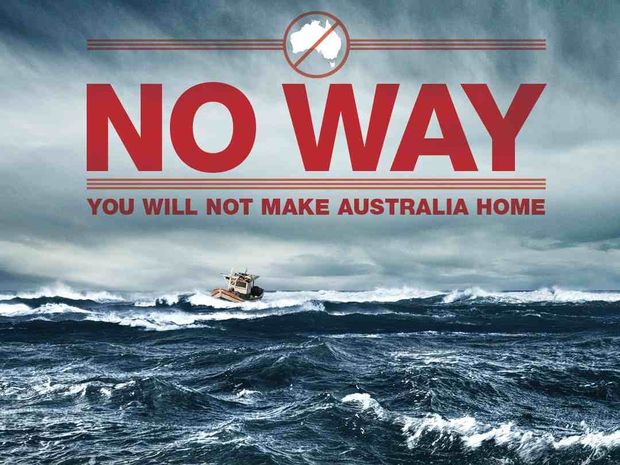

Governments play with refugees’ lives as if a sport. And Australia love its sport. Despite them not being criminals, they are treated so, and indeed have indefinite sentences imposed on them, such as the proposed lifetime ban on ever entering Australia, even as tourists. Just to illustrate how cracked this cup is, a report this week by a government-dominated committee found that “the ban would appear to apply a penalty on those who seek asylum and are part of the regional processing cohort.

“The right to seek asylum, irrespective of the mode of transit, is protected under international law.”

An “unlawful penalty” would be applied that breached the United Nations Refugee Convention.

Only recently the Prime Minister was exhorting Australia’s commitment to international law. Speaking of our offensive in cyberspace against Islamic State, he said the Australian Signals Directorate’s support . . . is subject to stringent legal oversight and is consistent with our support for the international rules-based order and our obligations under international law’’.

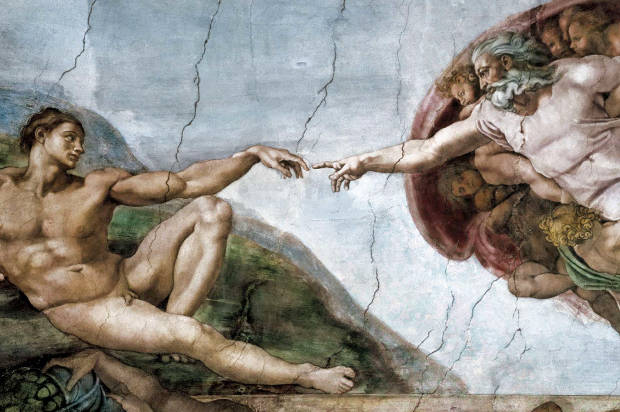

The concept of “our obligations under international law” is akin to Shakespeare’s view in Sonnet 116: that “Love is not love/Which alters when it alteration finds,/Or bends with the remover to remove:/O no; it is an ever-fixed mark.”

Australia’s international obligations are not in any sense true to the word’s definition; the only ever-fixed mark about them is the absence of a definition.

Peter Dutton says his point was that “we” and who the royal we is he doesn’t say, “should call out the small number within the community, within the Lebanese community, who are doing the wrong thing”. But why did he not perhaps append a note to his point and cut and dice every ethnic group in the cities and countryside and make a point about them, too, and their proclivities and engagements with police and crime? Everyone, after all, is a descendant of a migrant on this island.

Except one nation.

A representative of that nation, Indigenous MP Pat Dodson reacted to the “stupidity” of the language Mr Dutton used with this: “This is what words do – when you don’t understand and comprehend the difference between debate and prejudice.”

Into the mix came, of course, One Nation leader Pauline Hanson, who in a debate on free speech, said: “We are told time and time again that we must be tolerant.

“Well, I’ve had it up to here with my tolerance.”

This from the senator who said in her maiden speech to Parliament 20 years ago: “I believe we are in danger of being swamped by Asians. They have their own culture and religion, form ghettos and do not assimilate.”

And yet despite all, Australia is a multicultural success story. But these days, as ideology and bigotry and the truly nasty unedifying fight for righteousness and the moral high ground blazes, the thought keeps gnawing away, is that success on the surface or underneath it?

The national dialogue is now a shouting match. It has splintered into shards. It’s almost a bloodsport: the sins of the father versus those of the sons.

And we love our sport.

Warwick McFadyen is a freelance writer and editor

The pair came together in Redgum, and perhaps more than any other band, they sang of Australia, its soil and soul, its life in the cities and in the outback, its history, its politics. They were, out of laziness by some labelled a protest group, but their ethos ran deeper than that. They dug into the cultural and political and held up to the light the stones most would have preferred buried. Their first album was called If You Don’t Fight You Lose. It was a marker, from which they expanded with subsequent albums. They questioned. They were not afraid to sing out. They were a breath of fresh air.

The pair came together in Redgum, and perhaps more than any other band, they sang of Australia, its soil and soul, its life in the cities and in the outback, its history, its politics. They were, out of laziness by some labelled a protest group, but their ethos ran deeper than that. They dug into the cultural and political and held up to the light the stones most would have preferred buried. Their first album was called If You Don’t Fight You Lose. It was a marker, from which they expanded with subsequent albums. They questioned. They were not afraid to sing out. They were a breath of fresh air.

By Warwick McFadyen

By Warwick McFadyen You people deserve me. Day in, day out, I have been showing you the glories of my waves, and now, come the hour, you have granted me the highest honour. I salute you.

You people deserve me. Day in, day out, I have been showing you the glories of my waves, and now, come the hour, you have granted me the highest honour. I salute you.

By Warwick McFadyen

By Warwick McFadyen